Since 2014 we’ve cautioned investors about publicly traded marijuana stocks. Back then we cautioned would-be investors about “pot companies that are trading at frothy levels that are not well-positioned to compete in the marijuana marketplace.” More recently, we’ve written about the scale of mergers, acquisitions, and cross border work, how to “raise money right,” and how Canadian public companies invest in U.S. cannabis. Other posts have examined the challenges of cannabis startups in complying with securities laws and highlighted pending cannabis-related securities litigation.

Since 2014 we’ve cautioned investors about publicly traded marijuana stocks. Back then we cautioned would-be investors about “pot companies that are trading at frothy levels that are not well-positioned to compete in the marijuana marketplace.” More recently, we’ve written about the scale of mergers, acquisitions, and cross border work, how to “raise money right,” and how Canadian public companies invest in U.S. cannabis. Other posts have examined the challenges of cannabis startups in complying with securities laws and highlighted pending cannabis-related securities litigation.

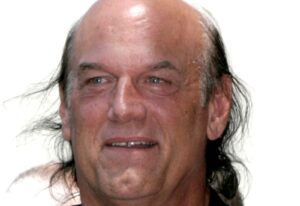

A significant player in the burgeoning hemp industry is Hemp, Inc. , (“Hemp”) a publicly traded company that trades between 50 and 100 million shares a day, according to its website, which also notes that its CEO, Bruce Perlowin, has been in the cannabis industry since at least 1978. Unfortunately, Hemp and others, including Perlowin, are the subject of a civil enforcement action filed in 2016 by the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) that is pending in the District Court of Nevada.

This post concerns a recent order (“Order”) in the SEC civil enforcement action by the federal magistrate which decided two motions for sanctions brought by the SEC against four of the defendants — Perlowin, Barry K. Epling and two entities he controls, Ferris Holdings, Inc. and Hobbes Equities, Inc. The SEC alleged these defendants fabricated evidence and gave false testimony at their depositions.

What is the lawsuit about? The SEC alleges that the defendants “engaged in a comprehensive, years-long scheme to defraud investors and evade securities law by selling restricted shares of Hemp without registering the sales.” They did so, says the SEC, by selling hundreds of millions of unregistered and purportedly unrestricted shares of Hemp to public investors and by exchanging gifts and entering into sham consulting agreements. Specifically, Epling—through entities he controls, Ferris and Hobbes—sold $9.8 million in securities, of which $1.8 million was used to pay expenses on behalf of Perlowin and Hemp. The defendants have claimed these payments were personal loans from Ferris to Perlowin.

The first motion concerned allegedly falsified evidence produced by Epling and false testimony given by Epling and Perlowin. To determine whether the consulting agreement were bona fide, the SEC asked Epling for copies of his filed tax returns between 2011-2015, including schedules and forms. Epling did not initially produce the requested documents and later produced tax documents that were unsigned and undated printouts bearing the watermark “DO NOT FILE.” The SEC then sought copies of his returns from the IRS and learned that Epling had filed returns for several years on the same day – May 5, 2017, nearly three months after the SEC made its discovery request, and after Epling had told the SEC he had just found his returns.

The SEC argued that the tax returns never existed and were in fact created by Epling in response to the SEC’s discovery request. The SEC characterized the returns as falsified evidence and sought to exclude them from trial. The SEC asked the court to impose an adverse inference and adverse jury instruction that the consulting agreements were not bona fide (effectively deciding this issue for trial). The SEC also sought sanctions against Perlowin and Epling for giving false deposition testimony. Both testified there were no documents memorializing the $1.8 million in loans. Yet several weeks later they produced copies of documents they claimed memorialized those same loans. The SEC asked the court to exclude all evidence related to the claimed loans and for an adverse instruction that there were no loans.

The second motion alleged that Ferris provided false evidence (tax returns) that were never actually filed with the IRS but were produced by Ferris to the SEC in response to a request for “as-filed” returns. For this offense and Epling’s other offenses, SEC sought the drastic sanction of terminating sanctions against Epling and the two defendant-companies he controls, Ferris and Hobbes. (This means the SEC believed the discovery violations so egregious that it asked the Court to enter default judgment against these defendants, effectively terminating the case as to these defendants without a trial.)

The Order is thorough, concluding that the defendants’ conduct was “egregious” and a waste of a “huge amount of judicial and party resources.” Nonetheless, the Court denied the SEC’s request for terminating sanctions, despite finding Perlowin and Epling’s testimony at the motions hearing not credible and that Epling deceived the SEC (and his own) counsel with respect to his tax returns. The defendants’ deception and discovery violations warranted sanctions, but were not enough to interfere with Epling and Ferris’s right to a trial on the merits, said the court.

Although these defendants may have escaped default judgment, I do not envy their counsel’s task at trial because the Court ruled that:

- Defendants are precluded from offering any evidence at hearing, in motion practice, or at trial related to the loan documents produced after Epling and Perlowin’s depositions;

- The jury should be instructed that the defendants failed to comply with their discovery obligations;

- The jury should be instructed that Epling deceived counsel for the SEC and defense counsel by falsely representing that his personal tax returns he produced for 2012-2014 were “as-filed” copies; and

- The jury should be instructed that they may consider evidence of the defendants’ discovery violations and Epling’s deception about his personal tax returns along with all other evidence in the case in reaching their verdict.

The moral of the story is here is plain: Don’t play fast and loose with the facts should you or your company find yourself the subjects of an SEC investigation. The chances of you succeeding at doing so are minimal. One wonders how long defense counsel—some of whom were deceived by their own clients—will continue this representation. A better strategy is to retain legal counsel and be forthright about the strengths and weaknesses of the SEC’s case (and your own) so that you and your legal team can implement the appropriate strategy.

(The defendants have since filed an objection to the magistrate’s order, which will now be reviewed by the trial judge.)