We are business and corporate lawyers, not criminal lawyers. This means we know enough about the law to tell someone when he or she may need criminal defense services, but we do not provide those services. Still, the specter of federal criminal charges is ever-present in the cannabis industry. When cannabis clients ask us about theoretical legal risks, we advise them that both civil and criminal liability exposure exist, on a spectrum from asset forfeiture to actual imprisonment. And we advise them that if they were charged for a violation of the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA), we would help them find them a criminal lawyer.

We are business and corporate lawyers, not criminal lawyers. This means we know enough about the law to tell someone when he or she may need criminal defense services, but we do not provide those services. Still, the specter of federal criminal charges is ever-present in the cannabis industry. When cannabis clients ask us about theoretical legal risks, we advise them that both civil and criminal liability exposure exist, on a spectrum from asset forfeiture to actual imprisonment. And we advise them that if they were charged for a violation of the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA), we would help them find them a criminal lawyer.

In Oregon, Washington and California, we represent large cannabis businesses and vanguard industry players. For this reason, ever since Donald Trump was elected—and especially once Jeff Sessions was appointed attorney general—the question of whether our clients could eventually need criminal lawyers became more likely than before. The theory among many lawyers and policy-makers, after all, is that if the federal government takes action, it would not start with state programs or even with individual users, but with marquee industry players.

It is well established under Supreme Court jurisprudence that the federal government can enforce the CSA against state-legal operators. It is also worth noting that the Rohrbacher-Blumenauer amendment only safeguards medical marijuana programs and participants. Therefore, if the feds sue an adult-use (“recreational”) operator and drag it into court, a jury would likely be instructed that if the operator traded in marijuana it had violated the CSA. And that is where things could get interesting.

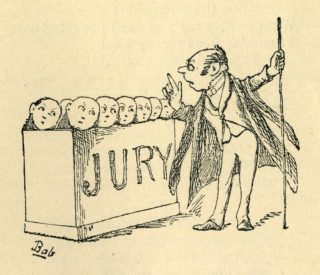

Most people—and even many lawyers—are surprised to learn that juries are not required to follow the law. When a jury’s conscience takes over and tells it that someone does not deserve criminal punishment for his or her actions, regardless of the law, the jury can choose to acquit. In legal terms, this is known as “jury nullification“: a systemic public safeguard from government run amok. To the chagrin of prosecutors, when jury nullification occurs, the Fifth Amendment’s Double Jeopardy Clause also prevents the acquitted person from being re-tried for the same charge.

Jury nullification has been a thorn in the side of state and federal prosecutors from our country’s early days. It became common in trials under the immensely unpopular Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which criminalized any action that interfered with the recovery of fugitive slaves by slave owners. It again became common in the 1920s, when the immensely unpopular Volstead Act criminalized alcohol possession, on the heels of the 18th Amendment. These examples beg a timely question: what other federal law has become immensely unpopular of late?

The possibility of jury nullification in a CSA case against a cannabis business is both fascinating and realistic. It is realistic not just because of the favorable polling for cannabis nationwide, but also because these juries would be empaneled in jurisdictions that voted to legalize pot in the first place. Imagine a hapless U.S. attorney being ordered to charge a popular cannabis farm in Humbolt County, California, which is America’s largest cannabis labor market. It would make for an interesting show, to say the least.

We tend to write more about law than policy on this blog, but the 29 states with medical marijuana programs, the 8 states with adult use programs, and the overlapping 46 states that allow some form of cannabis possession, are all acting at the direction of their citizens when it comes to marijuana, ignoring federal law. The Cole Memorandum, which has helped facilitate state-level legalization since 2013, likewise discounts federal law.

What’s to say a jury wouldn’t do the same? If you were on a jury would you convict for cannabis?

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article stems from a paper titled “Jury Nullification Risks for Federal Cannabis Enforcement: How History and Common Sense Protect the Recreational Marijuana Market.” The paper was written by Emily Baker, a third year student at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon.